Although it goes back centuries, the conflict in Northern Ireland experienced its darkest years between 1968 and 1998, during the period known as The Troubles, which left 3,500 dead. The complex causes of this conflict move between the religious, political and national; its consequences continue to mark the day-to-day political and social life of Northern Ireland.

The history of Northern Ireland has been marked since its inception in 1921 by a conflict between Republicans and Unionists, the former supporting the union of all Ireland into one state, the Republic of Ireland, the latter supporting the existence of Northern Ireland as a nation united with England, Scotland and Wales within the United Kingdom. These political positions are steeped in a markedly identitarian character: the Republicans are predominantly Catholic and ethnically Irish, while the Unionists are Protestant and ethnically Anglo-Scottish.

Keeping the island divided after independence from the Republic of Ireland was aimed at defending the interests of the Protestant population, which was concentrated in Ulster, the region in the far north of Ireland. This resulted in Northern Ireland is, from its inception, a politically unstable place where one part of the population, supported by the United Kingdom government, dominated the other part. This tension ended up generating an opposition among Catholics that was consolidated in 1968 in the struggle for civil rights in Northern Ireland.

Contents

The fight for Northern Ireland’s civil rights

The struggle for civil rights had its best example in the United States and Martin Luther King Jr., and there is no doubt that the Northern Irish case drank directly from that movement across the pond in the late 1960s. Driven also by that Parisian revolutionary spirit of May ’68, during the summer of that year, the Catholics of Northern Ireland began to protest against the discrimination they suffered with street demonstrations. This exclusion was eminently political and was manifested through an electoral system in which the delimitation of electoral districts was carefully calculated to ensure unionist dominance of the political system.

Discrimination against Catholics followed a pattern: in areas with a greater presence of Catholics and, therefore, a higher possibility of loss of unionist dominance, there was more discrimination. Although the discrimination was not only reflected in the electoral system, it was also evident in access to public housing and administrative positions, as in Londonderry County: at the time of the outbreak of the civil rights movement, the Catholic population exceeded 60 percent but held only 31.5 percent of public office.

Nor was this discrimination exclusively material. Irish identity was banned and silenced in Northern Ireland: official recognition of Irish nationality was denied, the use of its tricolor flag was outlawed, and Irish history and language were not included in the Northern Ireland education system. This denial of identity inevitably led to unrest and violence among Northern Irish Catholics, and marches to end discrimination against Catholics in Northern Ireland were frequent between the summers of 1968 and 1969. Protestant sectors of the country opposed them, and the marches often ended in confrontations between Catholics and Protestants or were dissolved by the security forces.

In this context of social tension, on August 12, 1969, a Protestant parade led to a major brawl after passing through the streets of the Catholic quarter of Bogside in Derry. The so-called Battle of the Bogside confronted Irish nationalists and the police forces of Northern Ireland for three days, which ended up requiring the direct intervention of the British Army. The battle of the Bogside is considered, given the intervention of the Army and the magnitude of the confrontations, the starting point of The Troubles. Three decades of conflict in a divided society whose effects still linger on in Northern Ireland politics.

The Troubles

There are three distinct actors in this armed conflict, which was especially fierce with the civilian population and which between 1969 and 1998 left 3,489 dead. In the first place, the Republican paramilitary groups stand out, with the IRA as the most relevant. The IRA (Irish Republican Army) is a terrorist organization initially formed in 1919 and reborn during The Troubles to reunify Ireland and build a socialist homeland on the island. Secondly, the UK state also played a key role in the conflict through its police forces and the British Army.

The last major actor is the unionist paramilitary groups, among which the UDA and the LVF stand out. The paramilitary groups believed that the state forces were not properly protecting the Protestant population and that their existence was necessary to fight the Republicans and thus prevent the reunification of Ireland. The Unionist groups had no clear political project and mainly sought to maintain the status quo and the Protestant character of Northern Ireland. These groups were, and continue to be, strongly linked with far-right currents and neo-Nazi groups throughout the United Kingdom.

After the battle of the Bogside, the IRA split up. On the one hand, the “officials” advocated a political solution for Irish unification and argued that this would not be possible until there were effective union and twinning between the Catholic and Protestant working classes in the north of Ireland. The “Provisional”, on the other hand, thought that the “officials” had failed in their methods of defending the Catholics of Northern Ireland and were determined to opt for armed struggle.

Violence increased dramatically from 1969 onwards. Clashes between paramilitaries, attacks on security forces and civilians, and political killings became routine. The year 1972 was the bloodiest year for The Troubles, leaving 480 dead. In addition, that year saw the famous January 30 known as Bloody Sunday, when fourteen demonstrators were shot dead by the British Army, and the less famous July 21 known as Bloody Friday, when the IRA detonated twenty-two bombs almost simultaneously, killing nine people. During 1972, the IRA significantly increased the intensity and frequency of its attacks, which eventually led, in March 1972, to the suspension of the self-government that the region had enjoyed since 1921. Northern Ireland would remain under direct control of London from then until the end of the conflict.

Unionist paramilitary groups began acting decisively as terrorist groups also in the early 1970s, committing attacks, and kidnapping and killing Catholics, civilians in most cases. Bombs in Republican pubs were common at that time. Subsequently, independent reports and investigations have shown the collaboration between these paramilitary groups and the British state forces. The nature of this collaboration ranges from the concealment and suppression of evidence to the direct involvement of members of the police and military forces in the killing of Republicans.

Five years after Bogside, in 1973, an attempt was made to end the conflict with the Sunningdale Agreement, which proposed a proportional sharing of power between the two communities and the creation of a new legislative body in Northern Ireland. However, the agreement was directly opposed by Unionist paramilitary groups and a significant section of the Protestant half of the country, as it threatened their political dominance over the region. In May 1974, after a two-week general strike by unionist workers in Northern Ireland, the agreement was deemed dead. Following the failure of Sunningdale, there was to be no further political agreement between the Republicans and the Unionists until 1998.

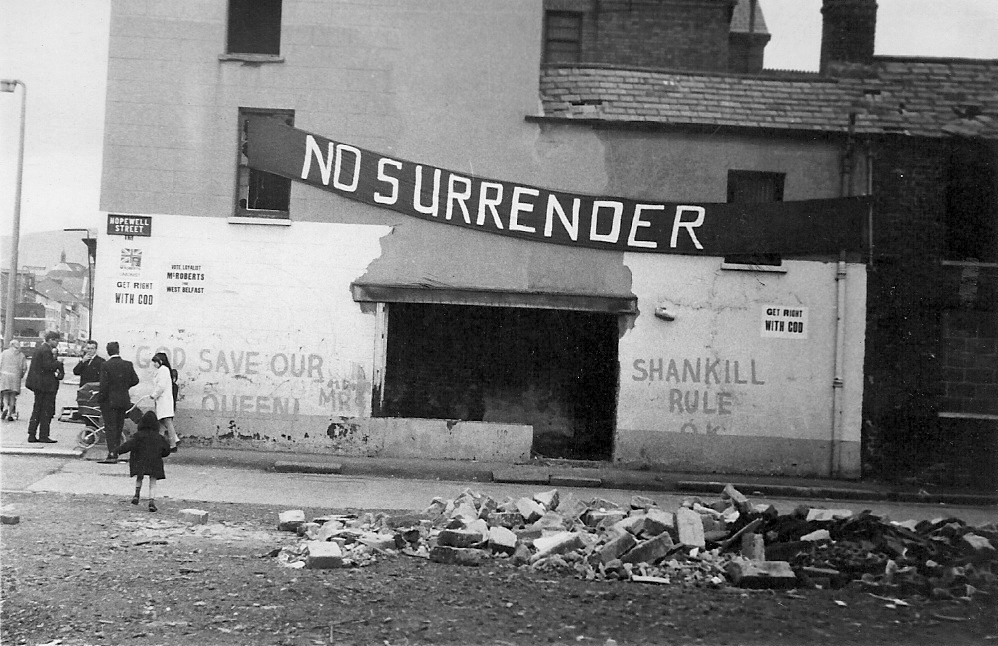

A banner calls for “no surrender” in the Unionist quarter of Shankill, Belfast. On the wall it reads “God save our queen”. Source: Wikimedia

A banner calls for “no surrender” in the Unionist quarter of Shankill, Belfast. On the wall it reads “God save our queen”. Source: Wikimedia

Despite the religious division between the opposing parties and the fact that The Troubles is usually treated as a conflict between Catholics and Protestants, its religious character was at best instrumental. For the Republican side, it was a war of national liberation, not a religious conflict; the continuation of the Irish war of independence (1919-1921), its final episode. Neither the IRA nor Sinn Féin, the political party that acted as its political arm, recognized British jurisdiction over Northern Ireland and therefore did not accept the British state as a legal entity with a monopoly on force, thus justifying the armed struggle.

Nor was the religious character a determining factor for the Unionist side, although religious fundamentalism was more evident on this side than on the Republican side. The political status of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom, and the threat that Republican groups posed to it, was what mobilized political, paramilitary and military action by the Unionist side.

Faced with the impossibility of ending the conflict, the British government changed its strategy in the late 1970s. After the failure of Sunningdale, London opted to try to reduce political violence and delegitimize the “national liberation struggle” discourse promoted by the IRA. Thus, the British military forces, seen by the Republicans as occupying forces, were progressively replaced by Northern Irish police forces. London also put an end to the doctrine of internment without trial and sought to delegitimize the charge that imprisoned Republicans were political prisoners. This also led to a change in the status of Republican prisoners, as they had previously been legally treated as prisoners of war, who have a number of privileges over ordinary prisoners based on international law.

The Republican prisoners responded to the change in conditions by protesting with hunger strikes, which culminated in the death of ten of them in 1981. These hunger strikes set off the British government’s attempt to move the discourse away from the “struggle for national liberation” and to frame the actions of the IRA as acts of bloodthirsty criminals. The hunger strikes reminded Catholics in Northern Ireland that there were people willing to die for an ideal, reviving the nationalist struggle.

Rifle and ballot box strategy

The IRA and Sinn Féin began coordinating their actions around this time, in what has been called the ballot box and Armalite strategy, which in Spanish would translate as ‘Urna y Armas’, the name of an American-made rifle typically used by Republican paramilitaries. This consisted of coordinating the violent actions of the IRA and the political participation of Sinn Féin, combining both to achieve Republican objectives. Thus, Sinn Féin took participants in the hunger strikes as party representatives, capitalizing on its popularity among Northern Irish Catholics.

As a result of this coordination strategy, violence decreased significantly during the 1980s, with fewer than 100 victims per year in most years of the decade. The exception was an increase in bomb attacks on English soil, most notably the attempted assassination of then-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in Brighton in 1984. Most of these explosions ended without death, as bomb warnings were usually given. The most frequent target during the decade was London’s financial district, as the economic damage to the victims was prioritized.

Unionist violence was also significantly reduced in those years. Following the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1985, which guaranteed the Republic of Ireland a consultative role in Northern Ireland, unionist paramilitary violence intensified again. However, in the face of a progressive loss of hope of achieving their objectives through armed means and exhausted after decades of intense conflict, both Republican and Unionist groups began to be open to dialogue and expressed their intention to end it in a peaceful and consultative manner in the late 1980s.

Good Friday Peace

The IRA unilaterally announced a ceasefire in 1994, and the main Unionist groups responded in the same way shortly afterward. However, Sinn Féin was initially denied participation in the peace negotiations, as it was seen as a way of giving a voice to the terrorists. In response, the IRA broke the ceasefire by detonating an explosive device in 1996. The return of violence demonstrated that not admitting one of the most relevant actors in the conflict to the table would prevent peace from being brought to Northern Ireland, and in 1997 Sinn Féin’s participation in the negotiation process was accepted, with the IRA once again announcing a new ceasefire.

These negotiations would crystallize in the Good Friday Agreement, also known as the Belfast Agreement, in 1998, which was ratified through two referenda held on May 22 1998, one in Northern Ireland and the other in the Republic of Ireland, the first with 71.1% support and the second with 94.4%. This agreement recognizes both British and Irish nationality in Northern Ireland, allows reopening of the border in the island of Ireland and restores self-government with a system of proportional representation of ministers according to the vote. The Northern Ireland police, closely linked to the abuse of Republicans during The Troubles, was replaced by a new police force with quotas for Catholics at the top. Perhaps the most important concession, however, is that it recognizes the right of the inhabitants of Northern Ireland to change the legal status of the territory through democratic means, legalizing the possibility of independence and accession to the Republic of Ireland through democratic mechanisms.

In general terms, the Good Friday Agreement benefited the Republican side more than the Unionist side, bearing in mind that the treaty accepts many of the Republican claims. Some go further and claim that the very nature and language used in the document legitimizes the Republican position and de facto justifies the armed struggle. This position is based on the fact that the concessions in the agreement seem to prove the Republicans right and accept the armed struggle as a legitimate means to achieve political ends. These include guaranteeing executive power to Sinn Féin without requiring the surrender of IRA weapons – which would end up being disarmed before international observers in 2005 – adopting Republican rhetoric in the text, or withdrawing extradition requests against wanted IRA members.

A peaceful and unstable Ireland

Peace and political stability did not come immediately after the agreement. Members of paramilitary groups on both sides refused to accept its legitimacy and created splits that continued to organize intermittent attacks to this day. In the twenty years following the agreement, 158 people were killed by these groups. At the political level, cooperation between forces of different persuasions was long overdue and political blockade became a feature of Northern Ireland politics during the early years of the new system. It was only in 2007, nine years after the agreement was signed, that the first stable government was formed in Northern Ireland, following cooperative efforts between the Unionist Chief Minister Ian Paisley and former IRA member Martin McGuinness.

However, the social divisions between Republicans and Unionists, Catholics and Protestants, remain deep. The unhealed wounds and hatred between the two halves of Northern Irish society still define the reality of the region, and political and social stability in Northern Ireland is under permanent threat. It is against this background that Northern Ireland voted by a majority to remain in the European Union in 2016; however, the majority of the British people opted for brexit.

This new challenge, that of the UK’s exit from the EU, puts the Good Friday Agreement at risk and, with it, the fragile balance of Northern Ireland. The brexit could re-establish a border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, which could have terrible economic, social and political consequences. On the one hand, Northern Ireland’s intimate economic relationship with the Republic of Ireland could be put at risk; on the other hand, an exit without an agreement would mean the violation of the peace agreement by the United Kingdom, which could trigger the spiral of violence once again. It is therefore not surprising that the problem of Northern Ireland has come back to the fore in the context of brexit, and has played a leading role in the negotiations. Peace in Northern Ireland must be respected with exquisite care: it is only twenty years since the conflict ended, and the monster could be reawakened.